Aversion and Desire

Enchiridion Chapter 2 / 53

I am making my way through each lesson in the Stoic philosopher Epictetus' handbook.

I want to expand and simplify the teachings for modern readers.

In the first chapter (read it here) we looked at the Dichotomy of Control—the Stoic categorising system for deciding what we should give our energy to.

In today's post, building on the last, we will examine Epictetus' views on how we should approach both desire and aversion as a practicing Stoic.

I/ Desire and Aversion: Root of Suffering

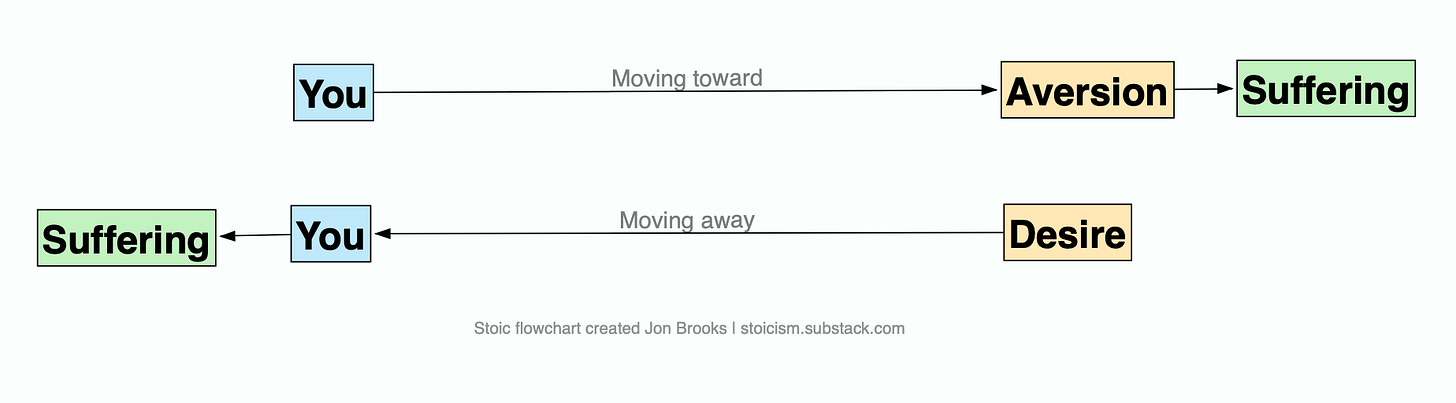

There are some things that we desire to move toward and some things that we desire to move away from.

We could say here for simplicity, that when we want to move toward something or possess something, we desire it and when the opposite is true, we feel aversion.

Desire and aversion are in many ways the roots of suffering.

If we fail to get what we desire or we experience that which we want to avoid, we become miserable.

The problem is, of course, because externals are largely out of our direct control, we will inevitably experience suffering in our life when we don’t get what we want.

So as a practicing Stoic, we must ask this important question:

If desire and aversion cause suffering, but desire and aversion are part of human nature, how can we protect ourselves from misery?

To answer this question, we will look at both aversion and desire separately.

II/ Working With Aversion

We feel aversion to certain things because we believe that by not avoiding that thing we will become miserable. The problem is, many of us who are not trained in Stoicism do not have an accurate sense of what will bring us contentment.

Sometimes we desire things that cause us misery, and sometimes we avoid things that would make us happier.

As a starting point for working with aversion, we should only seek to avoid or change things that are within our control, which we saw in Chapter One, include our judgments, impulses, desires, aversions, and mental faculties—internal things.

Conversely, we should not seek to avoid things outside of our control, which would include our body, our material possessions, and our reputation—external things.

What does this mean in practical terms?

It is foolish to try and avoid a situation over which you know you have no control, but it is wise to make changes to your judgments, impulses, desires, aversions, and mental faculties to reduce unnecessary suffering.

If you are desperate to avoid external misfortune such as illness, low status, and death you are setting yourself up for unhappiness. For such things out of our control, we would be well-advised to accept them and handle with wisdom.

If we want to live a happy life, the secret is to avoid thinking and acting poorly, and accept the world insofar as can’t control it, just as it is.

It is important to note here, that just because something is in our control, that doesn't automatically mean it should be avoided. We have to use discernment to figure out what is both within our control and good for our wellbeing.

Example: We may fear public spaces (agoraphobia), and seek to avoid public spaces. It’s within our control not to go outside, but is this way of living ideal for our longterm happiness and wisdom? No. A better approach would be to accept the world and other people (externals) as they are and to instead avoid thinking irrational thoughts and reconfiguring our goals (internal).

In short:

We should learn to actively desire any reality that is beyond our control because the alternative to doing this is to suffer in vein.

The things which we don't like that are within our control, we can modify.

Our ultimate desire should be to attain wisdom, which may paradoxically include the taming or transmutation of desire itself.

III/ Working With Desire

During your training to become a Stoic, drop desire to the fullest extent possible for the foreseeable future.

Desire is very powerful and can lead the untrained mind toward misery.

We can be miserable by not getting the things we want, but we can also become miserable by getting what we want if the desire was contrary to wisdom.

You could get something you desire, for example, but in attaining it the balance of your life gets disrupted. How many "privileged people" who frequently get what they want experience anger, impatience, sadness, frustration, and nihilism?

For now, do not fantasise about the things you want. Do not create a big wish list of material possessions and figure out clever plans to attain them. Just drop desire to the best of your abilities.

Instead, learn to desire what you already have and you will always be content.

In the flow of life when opportunities arise, answer to them a “yes” or a “no," and do not think too far ahead. Whenever you do act on a desire, do so with with self-discipline and calmness.

ENCHIRIDION CHAPTER TWO, EPICTETUS, TRANSLATION BY ROBERT DOBBIN:

[1] The faculty of desire purports to aim at securing what you want, while a version purports to shield you from what you don’t. If you fail in your desire, you are unfortunate, if you experience what you would rather avoid you are unhappy. So direct aversion only towards things that are under your control and alien to your nature, and you will not fall victim to any of the things that you dislike. But if your resentment is directed at illness, death or poverty, you are headed for disappointment.

[2] Remove it from anything not in our power to control, and direct it instead toward things contrary to our nature that we do control. As for desire, suspend it completely for now. Because if you desire something outside your control, you are bound to be disappointed; and even things we do control, which under other circumstances would be deserving of our desire, are not yet within our power to attain. Restrict yourself to choice and refusal; and exercise them carefully, with discipline and detachment.

I keep on coming back to my maxim that pain is inevitable but misery is optional. In terms of working with desire and aversion, I am made to think about the setting of expectations: that is, having a mental picture of an outcome that is good for what I desire or preferred to be averted. What comes up to me is the act of letting go, it's the acceptance regardless of the outcome. I am also being made aware of my tendencies of having no expectations as contrasted with expecting for the worst case scenario. This is where discernment comes in, by being able to 'think' of a worst case scenario, this allows me the opportunity to examine whether an action needs to be taken (pursue or avoid). If it's something that I can suffer with, then I'll take action. If not, then I'll let go (status quo or acceptance). After the decision has been made, it is then necessary to shift the focus outside the potential outcome, and back to 'real and actual world'. There's no more wallowing in the anxiety of a worst case scenario but instead be in the mode of having no expectations, and therefore be free from fear and anxiety.

I like that this article also pointed out that just because something that is not within our control doesn't mean we have to avoid it. This is where the act of courage comes in. Our default mode of reacting is to avoid any form of challenge because it can get uncomfortable and failure can mean death (in the form of embarrassment, shame or even physical pain). This is where discernment again comes in, if it does us good -- therefore this is something worth pursuing (for how else to unlock man's potential but to do something difficult and succeed in it?).

Stoicism therefore doesn't necessarily promote numbness nor mediocrity by letting go of things that is outside of our control. Rather, it promotes the use of rationality, to live with virtue -- do what is good, and the circumstances (the real world) unfold itself and BE -- instead of falling under the trap of fear and anxiety or not being able to function at all (which then hinders us to realize our potential).

Exercise the ability to say no to what is within one's control. Exercise the ability to say yes to choice, but not desire.